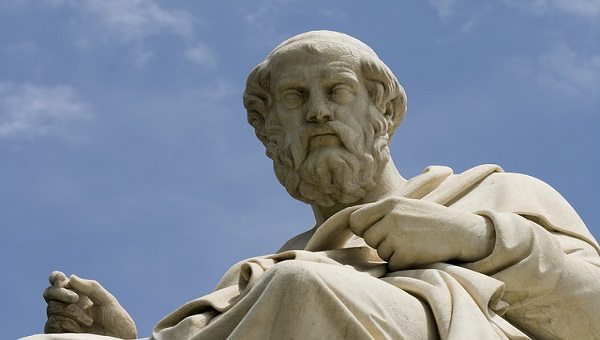

“You can discover more about a person in an hour of play than in a year of conversation”

– Plato–

The safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.

-Alfred North Whitehead (Process and Reality)–

PLATO and Aristotle were the most influential of all philosophers, ancient, medieval, or modern; and of the two, it was Plato who had the greater effect upon subsequent ages. I say this for two reasons: first, that Aristotle himself is an outcome of Plato; second, that Christian theology and philosophy, at any rate until the thirteenth century, was much more Platonic than Aristotelian. It is necessary, therefore, in a history of philosophic thought, to treat Plato, and to a lesser degree Aristotle, more fully than any of their predecessors or successors.

-Bertrand Russell (The History of Western Philosophy)

TOC

Facts

| Born | 428/427 or 424/423 BC Athens, Greece |

|---|---|

| Died | 348/347 BC (age c. 80) Athens, Greece |

| Notable work | Apology, Phaedo, Symposium & Republic |

| Era | Ancient philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Platonism |

|

Main interests

|

Rhetoric, art, literature, epistemology, justice, virtue, politics, education, family, militarism, friendship, love |

|

Notable ideas

|

Theory of Forms, Platonic idealism, philosopher king, Platonic realism, Plato’s tripartite theory of soul, hyperuranion, metaxy, khôra, methexis, theia mania, agathos kai sophos |

–

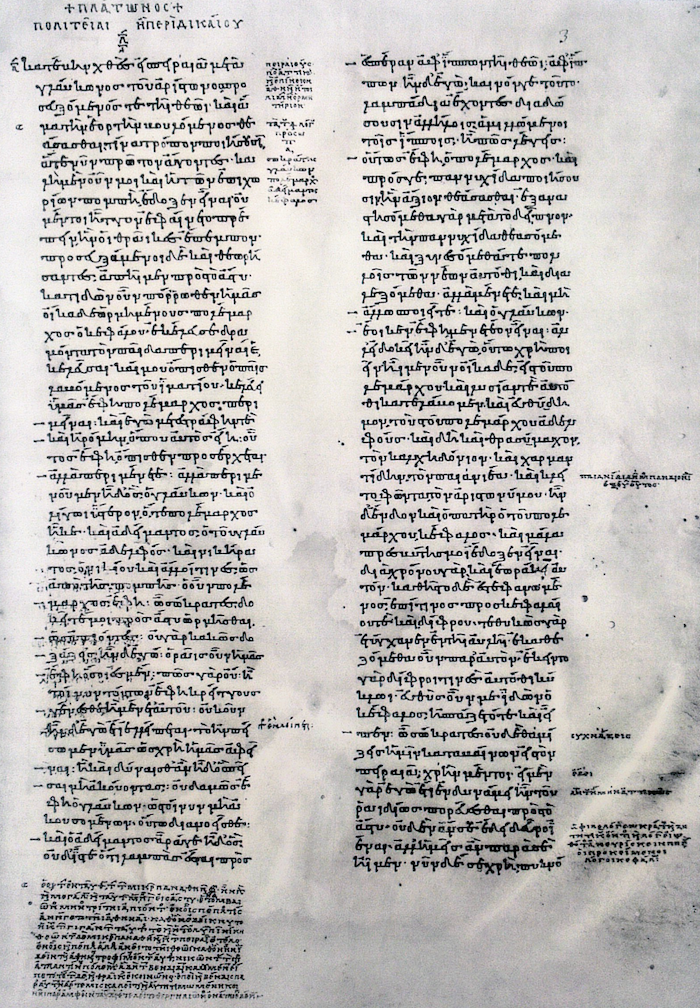

Plato (428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BCE) was a philosopher in Classical Greece and the founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. He is widely considered the most pivotal figure in the development of philosophy, especially the Western tradition. Unlike nearly all of his philosophical contemporaries, Plato’s entire work is believed to have survived intact for over 2,400 years.

Along with his teacher, Socrates, and his most famous student, Aristotle, Plato laid the very foundations of Western philosophy and science. Alfred North Whitehead once noted: “the safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.” In addition to being a foundational figure for Western science, philosophy, and mathematics, Plato has also often been cited as one of the founders of Western religion and spirituality. Friedrich Nietzsche, amongst other scholars, called Christianity, “Platonism for the people.” Plato’s influence on Christian thought is often thought to be mediated by his major influence on Saint Augustine of Hippo, one of the most important philosophers and theologians in the history of Christianity.

Some Famous Publications

- c.399–387 BCE Apology, Crito, Giorgias, Hippias Major, Meno, Protagoras (early dialogues)

- c.380–360 BCE Phaedo, Phaedrus, Republic, Symposium (middle dialogues)

- c.360–355 BCE Parmenides, Sophist, Theaetetus (late dialogues)

– - The Apology of Socrates is the Socratic dialogue that presents the speech of legal self-defence, which Socrates presented at his trial for impiety and corruption, in 399 BC.

- Meno is a Socratic dialogue. It appears to attempt to determine the definition of virtue, or arete, meaning virtue in general, rather than particular virtues, such as justice or temperance.

- Gorgias is a Socratic dialogue written by Plato around 380 BC. The dialogue depicts a conversation between Socrates and a small group of sophists (and other guests) at a dinner gathering. Socrates debates with the sophist seeking the true definition of rhetoric, attempting to pinpoint the essence of rhetoric and unveil the flaws of the sophistic oratory popular in Athens at the time.

– - Phædo or Phaedo, also known to ancient readers as On The Soul, is one of the best-known dialogues of Plato’s middle period. The Phaedo, which depicts the death of Socrates, is also Plato’s fourth and last dialogue to detail the philosopher’s final days, following Euthyphro, Apology, and Crito.

- The Symposium is a philosophical text by Plato dated c. 385–370 BC. It concerns itself at one level with the genesis, purpose and nature of love, and (in latter-day interpretations) is the origin of the concept of Platonic love.

– - The Republic is a Socratic dialogue, written by Plato around 380 BCE, concerning justice, the order and character of the just city-state and the just man. It is Plato’s best-known work, and has proven to be one of the world’s most influential works of philosophy and political theory, both intellectually and historically.

Selected Thoughts & Ideas

- The School of Life

- Wikipedia

- Bertrand Russell

- Will Durant

- The Philosophy Book (Big Ideas)

1. From The School of Life:

From Great Thinkers (The School of Life book):

- Plato devoted his life to one goal: helping people to reach a state of what he termed, or eudaimonia (fulfilment).

- Plato proposed that our lives go wrong in large part because we almost never give ourselves time to think carefully and logically enough about our plans.

- As Freud was happy to acknowledge, Plato was the inventor of therapy, insisting that we learn to submit all our thoughts and feelings to reason.

- As Plato repeatedly wrote, the essence of philosophy came down to the command to ‘know yourself’.

- Beautiful objects therefore have a really important function. They invite us to evolve in their direction, to become as they are. Beauty can educate our souls.

- Plato sees art as therapeutic: it is the duty of poets and painters (and, nowadays, novelists, television producers and designers) to help us lead good lives.

- He was the world’s first utopian thinker. .. Plato therefore wanted to give Athens new celebrities, replacing the current crop with ideally wise and good people he called ‘guardians’: models for everyone’s good development.

- The primary thing we need to learn is not just maths or spelling, but how to be good: we need to learn about courage, self-control, reasonableness, independence and calm.

- He founded a school called The Academy in Athens, which flourished for over 400 years. You went there to learn nothing less than how to live and die well.

- He proposed that a sizeable share of the next generation should be brought up by people more qualified than their own parents.

- Plato’s ideas remain deeply provocative and fascinating.

2. From Wikipedia:

- The State

Plato, through the words of Socrates, asserts that societies have a tripartite class structure corresponding to the appetite/spirit/reason structure of the individual soul.

- Productive (Workers) — the labourers, carpenters, plumbers, masons, merchants, farmers, ranchers, etc. These correspond to the “appetite” part of the soul.

- Protective (Warriors or Guardians) — those who are adventurous, strong and brave; in the armed forces. These correspond to the “spirit” part of the soul.

- Governing (Rulers or Philosopher Kings) — those who are intelligent, rational, self-controlled, in love with wisdom, well suited to make decisions for the community. These correspond to the “reason” part of the soul and are very few.

According to Plato, a state made up of different kinds of souls will, overall, decline from an aristocracy (rule by the best) to a timocracy (rule by the honorable), then to an oligarchy (rule by the few), then to a democracy (rule by the people), and finally to tyranny (rule by one person, rule by a tyrant).

Aristocracy is the form of government (politeia) advocated in Plato’s Republic. This regime is ruled by a philosopher king, and thus is grounded on wisdom and reason.

In timocracy the ruling class is made up primarily of those with a warrior-like character. In his description, Plato has Sparta in mind.

Oligarchy is made up of a society in which wealth is the criterion of merit and the wealthy are in control.

In democracy, the state bears resemblance to ancient Athens with traits such as equality of political opportunity and freedom for the individual to do as he likes.

Democracy then degenerates into tyranny from the conflict of rich and poor. It is characterized by an undisciplined society existing in chaos, where the tyrant rises as popular champion leading to the formation of his private army and the growth of oppression.

Check out: Plato’s five regimes

2. Metaphysics

“Platonism” is a term coined by scholars to refer to the intellectual consequences of denying, as Plato’s Socrates often does, the reality of the material world. In several dialogues, most notably the Republic, Socrates inverts the common man’s intuition about what is knowable and what is real. While most people take the objects of their senses to be real if anything is, Socrates is contemptuous of people who think that something has to be graspable in the hands to be real. In the Theaetetus, he says such people are eu amousoi, an expression that means literally, “happily without the muses” (Theaetetus 156a). In other words, such people live without the divine inspiration that gives him, and people like him, access to higher insights about reality.

Socrates says in the Republic that people who take the sun-lit world of the senses to be good and real are living pitifully in a den of evil and ignorance. Socrates admits that few climb out of the den, or cave of ignorance, and those who do, not only have a terrible struggle to attain the heights, but when they go back down for a visit or to help other people up, they find themselves objects of scorn and ridicule.

3. Bertrand Russel

With Plato’s account of Socrates, the difficulty is quite a different one from what it is in the case of Xenophon, namely, that it is very hard to judge how far Plato means to portray the historical Socrates, and how far he intends the person called “Socrates” in his dialogues to be merely the mouthpiece of his own opinions. Plato, in addition to being a philosopher, is an imaginative writer of great genius and charm. No one supposes, and he himself does not seriously pretend, that the conversations in his dialogues took place just as he records them. Nevertheless, at any rate in the earlier dialogues, the conversation is completely natural and the characters quite convincing. It is the excellence of Plato as a writer of fiction that throws doubt on him as a historian. His Socrates is a consistent and extraordinarily interesting character, far beyond the power of most men to invent; but I think Plato could have invented him. Whether he did so is of course another question.

The oracle of Delphi, it appears, was once asked if there were any man wiser than Socrates, and replied that there was not. Socrates professes to have been completely puzzled, since he knew nothing, and yet a god cannot lie. ….. He (Socrates) then went to the poets, and asked them to explain passages in their writings, but they were unable to do so. “Then I knew that not by wisdom do poets write poetry, but by a sort of genius and inspiration.” Then he went to the artisans, but found them equally disappointing. In the process, he says, he made many dangerous enemies. Finally he concluded that “God only is wise; and by his answer he intends to show that the wisdom of men is worth little or nothing; he is not speaking of Socrates, he is only using my name by way of illustration, as if he said, He, O men, is the wisest, who, like Socrates, knows that his wisdom is in truth worth nothing.”

The close connection between virtue and knowledge is characteristic of Socrates and Plato. To some degree, it exists in all Greek thought, as opposed to that of Christianity. In Christian ethics, a pure heart is the essential, and is at least as likely to be found among the ignorant as among the learned. This difference between Greek and Christian ethics has persisted down to the present day.

–

PLATO’S most important dialogue, the Republic, consists, broadly, of three parts. The first (to near the end of Book V) consists in the construction of an ideal commonwealth; it is the earliest of Utopias. One of the conclusions arrived at is that the rulers must be philosophers. Books VI and VII are concerned to define the word “philosopher.” This discussion constitutes the second section. The third section consists of a discussion of various kinds of actual constitutions and of their merits and defects.

–

“The society we have described can never grow into a reality or see the light of day, and there will be no end to the troubles of states, or indeed, my dear Glaucon, of humanity itself, till philosophers become rulers in this world, or till those we now call kings and rulers really and truly become philosophers, and political power and philosophy thus come into the same hands.”

― Plato, Plato’s Republic

4. Will Durant

To Plato, as to Bertrand Russell, mathematics is therefore the indispensable prelude to philosophy, and its highest form; over the doors of his Academy Plato placed, Dantesquely, these words, “Let no man ignorant of geometry enter here.”

-Will Durant

Plato´s aristocracy

We want to be ruled by the best, which is what aristocracy means ; have we not, Carlyle-like yearned and prayed to be ruled by the best? But we have come to think of aristocracies as hereditary: let it be carefully noted that this Platonic aristocracy is not of that kind ; one would rather call it a democratic aristocracy. For the people, instead of blindly electing the lesser of two evils presented to them as candidates by nominating cliques, will here be themselves, every one of them, the candidates; and will receive an equal chance of educational election to public office. There is no caste here; no inheritance of position or privilege; no stoppage of talent impecuniously born; the son of a ruler begins on the same level, and receives the same treatment and opportunity, as the son of a boot-black; if the ruler’s son is a dolt he falls at the first shearing ; if the boot-black’s son is a man of ability the way is clear for him to become a guardian of the state. Career will be open to talent wherever it is born. This is a democracy of the schools, a hundredfold more honest and more effective than a democracy of the polls.

By philosophy Plato means an active culture, wisdom that mixes with the concrete busy-ness of life; he does not mean a closeted and impractical metaphysician; Plato “is the man who least resembles Kant, which is (with all respect) a considerable merit.”

So our political structure will be topped with a small class of guardians; it will be protected by a large class of soldiers and “auxiliaries”; and it will rest on the broad base of a commercial, industrial, and agricultural population. This last or economic class will retain private property, private mates, and private families. But trade and industry will be regulated by the guardians to prevent excessive individual wealth or poverty; any one acquiring more than four times the average possession of the citizens must relinquish the excess to the state.

In short, the perfect society would be that in which each class and each unit would be doing the work to which its nature and aptitude best adapted it; in which no class or individual would interfere with others, but all would co- operate in difference to produce an efficient and harmonious whole. That would be a just state.

…Essentially he is right— is he not? what this world needs is to be ruled by its wisest men. It is our business to adapt hist hought to our own times and limitations. Today we must take democracy for granted we cannot limit the suffrage as Plato proposed; but we can put restrictions on the holding of office, and in this way secure that mixture of democracy and aristocracy which Plato seems to have in mind. We may accept without quarrel his contention that statesmen should be as specifically and thoroughly trained as physicians; we might establish departments of political science and administration in our universities; and when these departments have begun to function adequately we might make men ineligible for nomination to political office unless they were graduates of such political schools. We might even make every man eligible for an office who had been trained for it, and thereby eliminate entirely that complex system of nominations in which the corruption of our democracy has its seat; let the electorate choose any man who, properly trained and qualified, announces himself as a candidate. In this way democratic choice would be immeasurably wider than now, when Tweedledum and Tweedledee stage their quadrennial show and sham.

Finally, it is only fair to add that Plato understands that his Utopia does not quite fall within the practicable realm. He admits that he has described an ideal difficult of attainment ; he answers that there is nevertheless a value in painting these pictures of our desire; man’s significance is that he can image a better world, and will some part of it at least into reality ; man is an animal that makes Utopias. “We look before and after and pine for what is not.”

–

Justice / Ethics

Justice is not mere strength, but harmonious strength—desires and men falling into that order which constitutes intelligence and organization; justice is not the right of the stronger, but the effective harmony of the whole.

This is the goal of organization which every society must seek, if it would have life. Morality, said Jesus, is kindness to the weak; morality, said Nietzsche, is the bravery of the strong; morality, says Plato, is the effective harmony of the whole. Probably all three doctrines must be combined to find a per- fect ethic; but can we doubt which of the elements is fundamental?

From The Philosophy Book (Big Ideas)

Forms / shadows

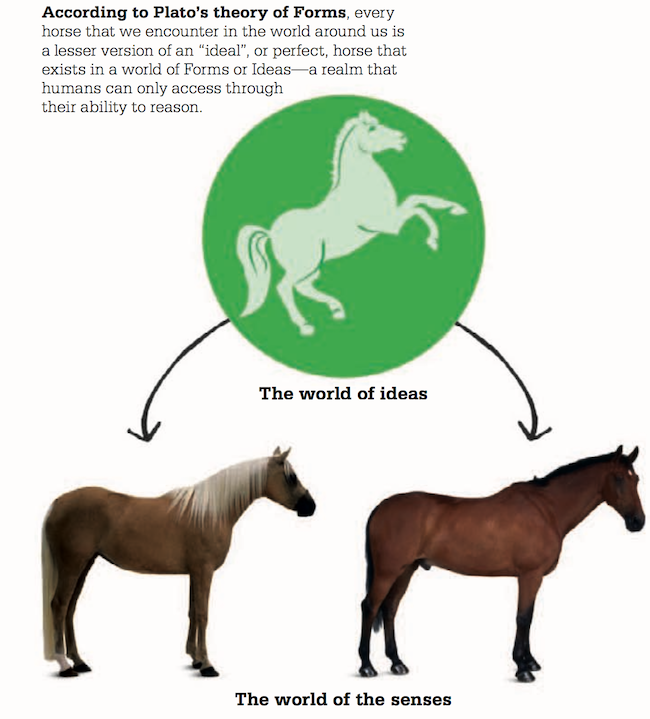

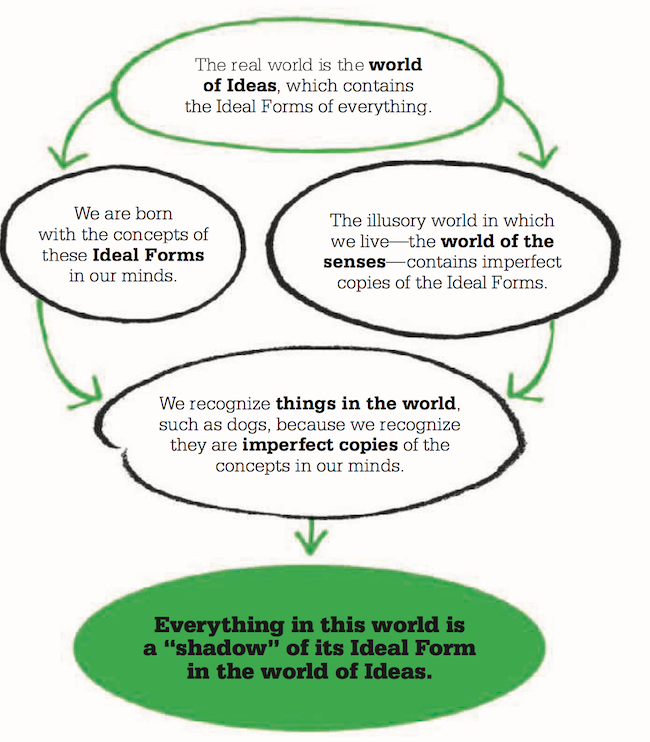

Plato talks about objects in the world around us, such as beds. When we see a bed, he states, we know that it is a bed and we can recognize all beds, even though they may differ in numerous ways. Dogs in their many species are even more varied, yet all dogs share the characteristic of “dogginess”, which is something we can recognize, and that allows us to say we know what a dog is. Plato argues that it is not just that a shared “dogginess” or “bedness” exists, but that we all have in our minds an idea of an ideal bed or dog, which we use to recognize any particular instance.

Reasoning brings Plato to only one conclusion—that there must be a world of Ideas, or Forms, which is totally separate from the material world. It is there that the Idea of the perfect “triangle”, along with the Idea of the perfect “bed” and “dog” exists. He concludes that human senses cannot perceive this place directly—it is only perceptible to us through reason. Plato even goes on to state that this realm of Ideas is “reality”, and that the world around us is merely modelled upon it.

Innate Knowledge

The problem remains of how we can come to know these Ideas, so that we have the ability to recognize the imperfect instances of them in the world we inhabit. Plato argues that our conception of Ideal Forms must be innate, even if we are not aware of this. He believes that human beings are divided into two parts: the body and the soul. Our bodies possess the senses, through which we are able to perceive the material world, while the soul possesses the reason with which we can perceive the realm of Ideas. Plato concludes that our soul, which is immortal and eternal, must have inhabited the world of Ideas before our birth, and still yearns to return to that realm after our death. So when we see variations of the Ideas in the world with our senses, we recognize them as a sort of recollection. Recalling the innate memories of these Ideas requires reason—an attribute of the soul.

Unsurpassed legacy

Plato himself was the embodiment of his ideal, or true, philosopher. He argued on questions of ethics that had been raised previously by the followers of Protagoras and Socrates, but in the process, he explored for the first time the path to knowledge itself. He was a profound influence on his pupil Aristotle—even if they fundamentally disagreed about the theory of Forms. Plato’s ideas later found their way into the philosophy of medieval Islamic and Christian thinkers, including St. Augustine of Hippo, who combined Plato’s ideas with those of the Church. By proposing that the use of reason, rather than observation, is the only way to acquire knowledge, Plato also laid the foundations of 17th-century rationalism. Plato’s influence can still be felt today— the broad range of subjects he wrote about led the 20th-century British logician Alfred North Whitehead to say that subsequent Western philosophy “consists of a set of footnotes to Plato.”

Quotes

“The heaviest penalty for declining to rule is to be ruled by someone inferior to yourself.”

― Plato, The Republic“I am the wisest man alive, for I know one thing, and that is that I know nothing.”

― Plato, The Republic“That man is wisest who, like Socrates, realizes that his wisdom is worthless” – Plato

“The beginning is the most important part of the work.”

― Plato, The Republic“Love is simply the name for the desire and pursuit of the whole.”

― Plato, The Symposium“For this feeling of wonder shows that you are a philosopher, since wonder is the only beginning of philosophy.”

― Plato, Theaetetus

Videos / Audio

PHILOSOPHY – The Good Life: Plato – Chris Surprenant (University of New Orleans)

–

Will Durant – The Philosophy of Plato

–

Giants of Philosophy – Plato

Sources

- Wikipedia

- Bertrand Russell – History of Western Philosophy

- Will Durant – The Story of Philosophy

- Great Thinkers (The School of Life book)

- Buckingham, King, Burnaham… – The Philosophy Book (Big Ideas)

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (website)

- History of Philosophy (King´s College London – website)

- The Basics of Philosophy (website)

- The School of Life website -> theschooloflife.com

-Egil