“Irvine excels at giving a “walking tour” of the many schools of Stoic philosophy, from Greek to Roman traditions, identifying individual Stoic thinkers (many more than Seneca) and their principles and techniques, which Irvine argues are even more relevant in modern times than their own.”

–Philosophical Practice“Well-written and so compelling, this is a rare example of a book that actually will make a difference in the lives of its readers. Whether it’s coping with grief or arriving at lasting happiness, Irvine shows, with care and verve, ancient Stoic wisdom to be ever relevant and very, very helpful.”

–Gary Klein, author of Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions“Bill Irvine has given us a great gift: the most accessible and inviting description of modern Stoicism available. Read this book and be prepared to change your life!”

–Sharon Lebell, author of Epictetus’s The Art of Living: The Classical Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness

TOC

- Introduction: A Plan for Living

- Part One: The Rise of Stoicism

- One: Philosophy Takes an Interest in Life

- Two: The First Stoics

- Three: Roman Stoicism

- Part Two: Stoic Psychological Techniques

- Four: Negative Visualization: What’s the Worst That Can Happen?

- Five: The Dichotomy of Control: On Becoming Invincible

- Six: Fatalism: Letting Go of the Past . . . and the Present

- Seven: Self-Denial: On Dealing with the Dark Side of Pleasure

- Eight: Meditation: Watching Ourselves Practice Stoicism

- Part Three: Stoic Advice

- Nine: Duty: On Loving Mankind

- Ten: Social Relations: On Dealing with Other People

- Eleven: Insults: On Putting Up with Put-Downs

- Twelve: Grief: On Vanquishing Tears with Reason

- Thirteen: Anger: On Overcoming Anti-Joy

- Fourteen: Personal Values: On Seeking Fame

- Fifteen: Personal Values: On Luxurious Living

- Sixteen: Exile: On Surviving a Change of Place

- Seventeen: Old Age: On Being Banished to a Nursing Home

- Eighteen: Dying: On a Good End to a Good Life

- Nineteen: On Becoming a Stoic: Start Now and Prepare to Be Mocked

- Part Four: Stoicism for Modern Lives

- Twenty: The Decline of Stoicism

- Twenty-One: Stoicism Reconsidered

- Twenty-Two: Practicing Stoicism

- A Stoic Reading Program

–

Quotes From the Book

Introduction: A Plan for Living

But a grand goal in living is the first component of a philosophy of life. This means that if you lack a grand goal in living, you lack a coherent philosophy of life.

I had long been intrigued by Zen Buddhism and imagined that on taking a closer look at it in connection with my research, I would become a full-fledged convert. But what I found, much to my surprise, was that Stoicism and Zen have certain things in common.

Furthermore, I came to realize that Stoicism was better suited to my analytical nature than Buddhism was. As a result, I found myself, much to my amazement, toying with the idea of becoming, instead of a practicing Zen Buddhist, a practicing Stoic.

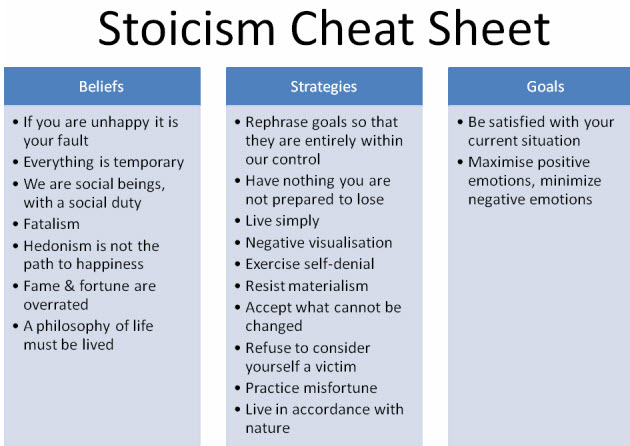

I discovered, though, that the goal of the Stoics was not to banish emotion from life but to banish negative emotions.

There was also agreement that one wonderful way to tame our tendency to always want more is to persuade ourselves to want the things we already have.

We will reconsider our goals in living. In particular, we will take to heart the Stoic claim that many of the things we desire—most notably, fame and fortune—are not worth pursuing.

And when they encounter Epictetus’s observation that some things are up to us and some things are not, and that if we have any sense at all, we will focus our energies on the things that are up to us

Part One: The Rise of Stoicism

One: Philosophy Takes an Interest in Life

classicist Francis MacDonald Cornford describes Socrates’ philosophical significance in similar terms: “Pre-Socratic philosophy begins … with the discovery of Nature; Socratic philosophy begins with the discovery of man’s soul.”

But even though schools of philosophy are a thing of the past, people are in as much need of a philosophy of life as they ever were.

Furthermore, whatever philosophy of life a person ends up adopting, she will probably have a better life than if she tried to live—as many people do—without a coherent philosophy of life

Two: The First Stoics

The Stoics’ interest in logic is a natural consequence of their belief that man’s distinguishing feature is his rationality.

Ethics was the third and most important component of Zeno’s Stoicism.

It is concerned not with moral right and wrong but with having a “good spirit,” that is, with living a good, happy life or with what is sometimes called moral wisdom.

If we lived in perfect accordance with nature—if, that is, we were perfect in our practice of Stoicism—we would be what the Stoics refer to as a wise man or sage.

Stoic tranquility was a psychological state marked by the absence of negative emotions, such as grief, anger, and anxiety, and the presence of positive emotions, such as joy.

Roman Stoics had less confidence than the Greeks in the power of pure reason to motivate people.

By highlighting tranquility in their philosophy, the Stoics not only made it more attractive to ancient Romans but made it, I think, more attractive to modern individuals as well.

Three: Roman Stoicism

According to Epictetus, the primary concern of philosophy should be the art of living:

Begin each day by telling yourself: Today I shall be meeting with interference, ingratitude, insolence, disloyalty, ill-will, and selfishness – all of them due to the offenders’ ignorance of what is good or evil.

Part Two: Stoic Psychological Techniques

Four: Negative Visualization: What’s the Worst That Can Happen?

We humans are unhappy in large part because we are insatiable; after working hard to get what we want, we routinely lose interest in the object of our desire. Rather than feeling satisfied, we feel a bit bored, and in response to this boredom, we go on to form new, even grander desires. The psychologists Shane Frederick and George Loewenstein have studied this phenomenon and given it a name: hedonic adaptation.

As a result of the adaptation process, people find themselves on a satisfaction treadmill.

In other words, we need a technique for creating in ourselves a desire for the things we already have.

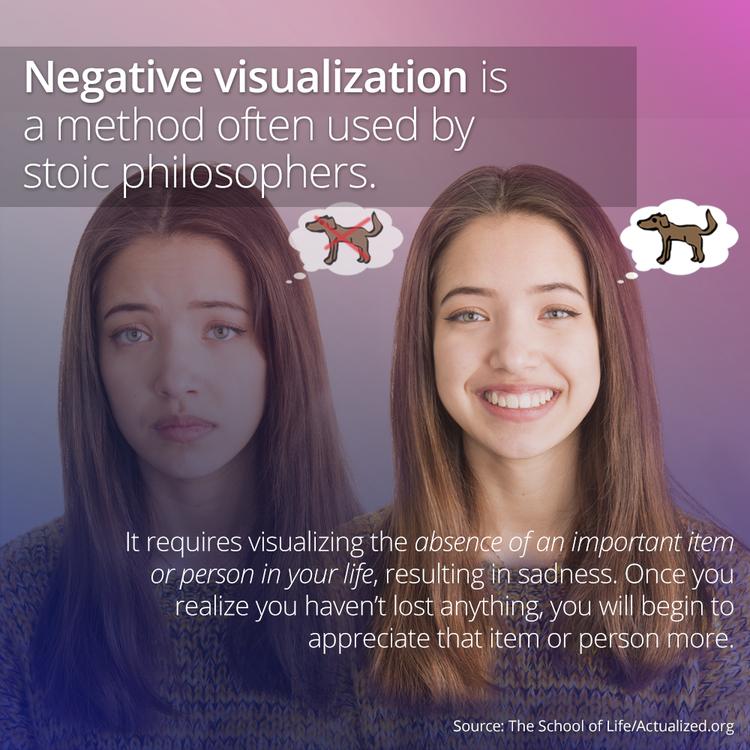

negative visualization—was employed by the Stoics at least as far back as Chrysippus. It is, I think, the single most valuable technique in the Stoics’ psychological tool kit.

What we find, though, is that the regular practice of negative visualization has the effect of transforming Stoics into full-blown optimists.

But understood properly, saying grace—and for that matter, offering any prayer of thanks—is a form of negative visualization.

Furthermore, there is a difference between contemplating something bad happening and worrying about it. Contemplation is an intellectual exercise, and it is possible for us to conduct such exercises without its affecting our emotions.

It teaches us, in other words, to enjoy what we have without clinging to it.

we are forced to recognize that every time we do something could be the last time we do it, and this recognition can invest the things we do with a significance and intensity that would otherwise be absent.

Negative visualization is therefore a wonderful way to regain our appreciation of life and with it our capacity for joy.

Five: The Dichotomy of Control: On Becoming Invincible

OUR MOST IMPORTANT CHOICE in life, according to Epictetus, is whether to concern ourselves with things external to us or things internal.

make it your goal to want only those things that are easy to obtain—and ideally to want only those things that you can be certain of obtaining.

EPICTETUS’S HANDBOOK OPENS, somewhat famously, with the following assertion: “Some things are up to us and some are not up to us.”

There are things over which we have complete control, things over which we have no control at all, and things over which we have some but not complete control.

Thus, wanting things that are not up to us will disrupt our tranquility, even if we end up getting them. In conclusion, whenever we desire something that is not up to us, our tranquility will likely be disturbed: If we don’t get what we want, we will be upset

To begin with, I think we have complete control over the goals we set for ourselves.

Another thing I think we have complete control over is our values.

It will clearly make sense for us to spend time and energy setting goals for ourselves and determining our values.

When it comes to other, more significant aspects of his life, a Stoic will likewise be careful in the goals he sets for himself.

The Stoics, as I have explained, were very much interested in human psychology and were not at all averse to using psychological “tricks” to overcome certain aspects of human psychology, such as the presence in us of negative emotions.

He will instead concern himself with things over which he has complete control and things over which he has some but not complete control. And when he concerns himself with things in this last category, he will be careful to set internal rather than external goals for himself and will thereby avoid a considerable amount of frustration and disappointment.

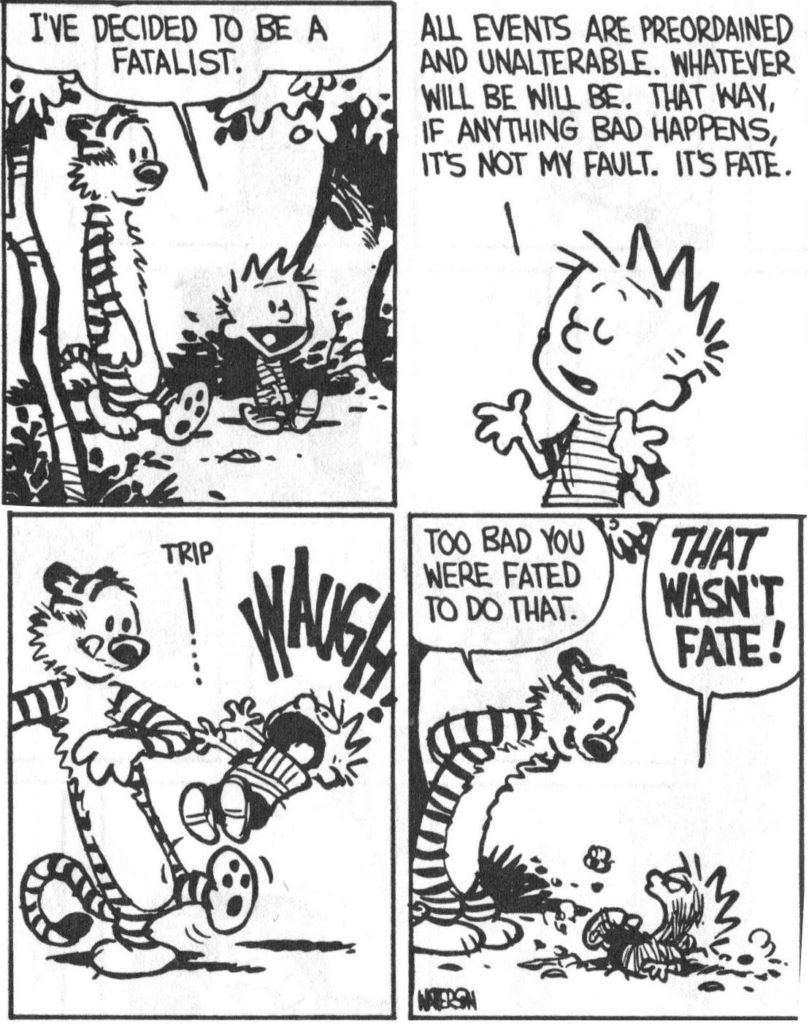

Six: Fatalism: Letting Go of the Past . . . and the Present

Epictetus: “we should keep firmly in mind that we are merely actors in a play written by someone else—more precisely, the Fates.”

Like most ancient Romans, the Stoics took it for granted that they had a fate.

For ancient Romans, then, life was like a horse race that is fixed: The Fates already knew who would win and who would lose life’s contests.

When the Stoics advocate fatalism, they are, I think, advocating a restricted form of the doctrine. More precisely, they are advising us to be fatalistic with respect to the past, to keep firmly in mind that the past cannot be changed.

Fatalism with respect to the past will doubtless be far more palatable to modern individuals than fatalism with respect to the future. Most of us reject the notion that we are fated to live a certain life; we think, to the contrary, that the future is affected by our efforts.

Notice that the advice that we be fatalistic with respect to the past and the present is consistent with the advice, offered in the preceding chapter, that we not concern ourselves with things over which we have no control. We have no control over the past; nor do we have any control over the present, if by the present we mean this very moment.

–

Seven: Self-Denial: On Dealing with the Dark Side of Pleasure

The Stoics, by way of contrast, welcomed a degree of discomfort in their life. What the Stoics were advocating, then, is more appropriately described as a program of voluntary discomfort than as a program of self-inflicted discomfort.

What Stoics discover, though, is that willpower is like muscle power: The more they exercise their muscles, the stronger they get, and the more they exercise their will, the stronger it gets.

–

Part Three: Stoic Advice

Nine: Duty: On Loving Mankind

They thought that man is by nature a social animal and therefore that we have a duty to form and maintain relationships with other people, despite the trouble they might cause us.

Therefore, in all I do, I must have as my goal “the service and harmony of all.” More precisely, “I am bound to do good to my fellow-creatures and bear with them.”

Indeed, when we awaken in the morning, rather than lazily lying in bed, we should tell ourselves that we must get up to do the proper work of man, the work we were created to perform.

The biggest obstacle to Marcus’s practice of Stoicism, though, appears to have been his rather intense dislike of humanity.

He remarks that when someone says he wants to be perfectly straightforward with us, we should be on the lookout for a concealed dagger.

For now, let me say this: Throughout the millennia and across cultures, those who have thought carefully about desire have drawn the conclusion that spending our days working to get whatever it is we find ourselves wanting is unlikely to bring us either happiness or tranquility.

–

Ten: Social Relations: On Dealing with Other People

In other words, by letting ourselves become annoyed, we only make things worse.

–

Eleven: Insults: On Putting Up with Put-Downs

we would be foolish to let the insults of these childish adults upset us. In other cases, we will find that those insulting us have deeply flawed characters. Such people, says Marcus, rather than deserving our anger, deserve our pity.

As a result, he says, “another person will not do you harm unless you wish it; you will be harmed at just that time at which you take yourself to be harmed.”

Therefore, if something external harms me, it is my own fault: I should have adopted different values.

It is therefore a response that is likely to deeply frustrate the insulter. For this reason, a humorous reply to an insult can be far more effective than a counterinsult would be.

The Stoics realized this and as a result advocated a second way to respond to insults: with no response at all.

–

Thirteen: Anger: On Overcoming Anti-Joy

Thus, when we feel ourselves getting angry about something, we should pause to consider its cosmic (in)significance. Doing this might enable us to nip our anger in the bud.

Fifteen: Personal Values: On Luxurious Living

Finally, Musonius advises us to follow the example set by Socrates: Rather than living to eat—rather than spending our life pursuing the pleasure to be derived from food—we should eat to live.

generally, it is perfectly acceptable, says Seneca, for a Stoic to acquire wealth, as long as he does not harm others to obtain it. It is also acceptable for a Stoic to enjoy wealth, as long as he is careful not to cling to it. The idea is that it is possible to enjoy something and at the same time be indifferent to it.

The Buddhist viewpoint regarding wealth, by the way, is very much like the view I have ascribed to the Stoics: It is permissible to be a wealthy Buddhist, as long as you don’t cling to your wealth.

Nineteen: On Becoming a Stoic: Start Now and Prepare to Be Mocked

In part because by adopting one, whether it be Stoicism or some rival philosophy, a person is demonstrating that he has different values than they do. They might therefore infer that he thinks their values are somehow mistaken, which is something people don’t want to hear.

If these people can get the convert to abandon his philosophy of life, the implied challenge will vanish, and so they set about mocking him in an attempt to make him rejoin the unreflecting masses.

Along with avoiding negative emotions, we will increase our chances of experiencing one particularly significant positive emotion: delight in the world around us.

Twenty: The Decline of Stoicism

Because of these similarities, Stoics and Christians found themselves competing for the same potential adherents.

In this competition, however, Christianity had one big advantage over Stoicism: It promised not just life after death but an afterlife in which one would be infinitely satisfied for an eternity.

The Stoics, on the other hand, thought it possible that there was life after death but were not certain of it, and if there was indeed life after death, the Stoics were uncertain what it would be like.

but the Stoics understood that there is at best a loose connection between our external circumstances and how happy we are.

If you consider yourself a victim, you are not going to have a good life; if, however, you refuse to think of yourself as a victim—if you refuse to let your inner self be conquered by your external circumstances—you are likely to have a good life, no matter what turn your external circumstances take.

And rather than wanting new things, we need to work at wanting the things we already have.

Twenty-One: Stoicism Reconsidered

If our goal is not merely to survive and reproduce but to enjoy a tranquil existence, the pain associated with a loss of social status isn’t just useless, it is counterproductive.

Stoicism, understood properly, is a cure for a disease. The disease in question is the anxiety, grief, fear, and various other negative emotions that plague humans and prevent them from experiencing a joyful existence.

As I explained in the introduction to this book, there was a time when I was attracted to Zen Buddhism as a philosophy of life, but the more I learned about Zen, the less attractive it became. In particular, I came to realize that Zen is incompatible with my personality. I am a relentlessly analytical person. For Zen to work for me, I would have to abandon my analytical nature.

Twenty-Two: Practicing Stoicism

Furthermore, by refusing to play the insult game—by refusing to respond to an insult with a counterinsult—I make it clear that I regard myself as being above such behavior. My refusal to play the insult game will likely irritate the insulter more than a counterinsult would.

lifestyle simplification is a process best left to advanced Stoics.

-Egil